Malandarri band rehearsal, featuring lead singer Samuel Evans

Jardine Andrew Kiwat was a transient 19-year-old Islander picking grapes in the Riverland when he had his first brush with the Centre for Aboriginal Studies in Music (CASM) in Adelaide.

It was the ‘80s, and word on the street was a band in the city needed a drummer. The Darnley and South Sea Islander man, originally from the sugar-cane coastal Queensland town of Mackay, tapped on any surface he could find from the age of five. He had a passion for percussion. He was in.

Bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, Jardine drove hours to get to the rehearsal space – a disused soup kitchen on Pulteney Street – and picked up his sticks. The practice bore fruit. Not only did it renew his love for music, but during the session someone told him about a place on the outskirts of Adelaide offering Aboriginal people free music tuition. From then, Jardine was locked into CASM’s groove, where he stayed for three decades.

“A lot of us talked about it when we came down here,” he says about those early years, “that you don’t know why you left home but you had to go and do something.”

Ethnomusicologist Catherine Ellis and Ngarrindjeri poet and musician Leila Rankine started CASM in 1972 as an ad-hoc, co-curricular music program headquartered in Port Adelaide.

The aim was simple: create a music program to get young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people off the streets and out of trouble. Over the next 50 years, it then became a hub where First Nations students could learn to express themselves through music and realise their potential as musicians.

Around the time CASM was germinating, Australia was in the midst of great social upheaval. Governments, churches, and welfare bodies officially stopped the forcible removal of Aboriginal children in 1970, and in 1974 the Federal Government abolished university fees.

A year later, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam famously poured red sand into the hand of Gurindji man Vincent Lingiari. It was the first time land had been returned to an Aboriginal community by the Commonwealth Government. These policies percolated through CASM and provided fertile socio-political ground for the school to stand on.

Across the country, news spread that a post-high school program dedicated to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music – the only of its kind back then, and the only of its kind now – was accepting students. Plucky aspirant First Nations musicians flew, drove, and hitchhiked from as far as the Top End, Tasmania and Torres Strait to join the ruckus.

In 1975, the University of Adelaide formally recognised the program’s potential and absorbed it into the Elder Conservatorium of Music. Pitjantjatjara Elder and songman Minjunga Baker was appointed as senior lecturer at the university that year too – a ground-breaking role at the time.

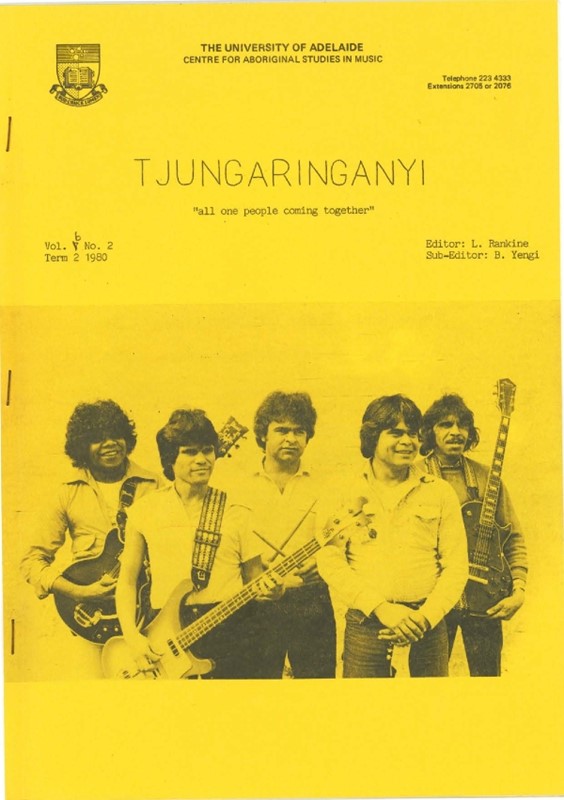

A 1980 edition of Tjungaringanyi

In each school term from 1972 to 1992, CASM released a newsletter called Tjungaringanyi, meaning coming together in Pitjantjatjara. In the first edition, Leila Rankine penned her initial thoughts on the program.

“I am seeing changes within the group, within the individual students, who are regarded as being almost unteachable or unreachable and who are responding to music,” she wrote. “It isn’t something which happens overnight, but it is happening.”

After playing in numerous bands and transforming a University of Adelaide rowing shed into a performance space, Jardine graduated from CASM. His certificate states he undertook training in “drums and tribal singing”, he says, laughing at the latter’s problematic phrasing. Following Jardine’s education, he then became a teacher, saying he was plucked out of the crowd by the program’s matriarchs.

This transition, Jardine believes, is part of the magic underpinning CASM’s success: the program was mostly led by Indigenous people, and was designed to give young Indigenous people, who almost always had no formal education, a chance.

The school recognised something in these individuals White Australia could not.

“At CASM, you can see the potential in someone when they can’t see it in themselves, and I didn’t see any potential for me,” Jardine says. “But they recognised the potential in me.”

Non-Indigenous educator Doug Petherick started working at CASM as a guitar teacher in 1988. Wearing a neat blue shirt and black pants, the now part-time University of Adelaide archivist joined the institution as it was pumping out political firebrand bands such as No Fixed Address, Coloured Stone, and Us Mob.

“There were times when the music was saying some gutsy stuff that the Australian community wasn’t able to handle,” he says.

Doug was drawn to CASM because of what was going on outside the classroom. It was the extra mile the educators were putting in for their pupils, supported by ample Federal Government funding. This included 10-day trips to the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands, where students learned Inma (cultural songs and dances) from Elders. It also spanned musical showcases with high-flying musicians, such as Warumpi Band, and introducing incarcerated Aboriginal juveniles to the organisation.

Back then, Doug reckons there was political blood coursing through CASM’s veins.

“There was a concerted desire to try and do something a bit more significant in the educational context broadly for Indigenous Australia,” he says. The program’s heyday was in the 1980s, with Doug recalling the cohort swelled to 56 students and was buttressed by its most secure funding. By then, CASM offered a three-year advanced diploma and one-year certificates for students. A degree was also in the pipeline. Despite CASM’s popularity, this never happened.

“The program had to start shrinking,” Doug says. He blames funding cuts to the uni sector and a scaling back of Commonwealth support for all schools.

As a result, CASM gutted the three-year advanced diploma, only offering a 12-month foundation course which would allow musicians to enter into the Elder Conservatorium’s other degrees after completion. This is what CASM offers now, under the banner of the University of Adelaide’s National Centre for Aboriginal Languages and Music Studies.

Grayson Rotumah, a tall, gregarious South Pacific Island and Bundjalung man, has coordinated the program since 1997. He wears his job with pride. Literally. You will often find Grayson walking around the University of Adelaide campus with a cap emblazoned with “CASM” in red and orange stitching. Despite this pride, Grayson is worried the program’s one-year structure could be setting students up to fail.

“These Indigenous kids need that structural support,” he explains. “And there is no pernicious nature of the university to cut or cull Indigenous programs, but I believe there could be some more support around this area.”

Grayson never envisaged a career in education. He left high school in Year 9 and spent his early adulthood working on farms, picking sweet potato, and bumbling around the Gold Coast in bands. But a fortuitous, if painful, injury led him south.

“I was working on the Gold Coast City Council, Tweed Shire Council, and was digging potholes on the beach for plants, and put a crowbar through my toe,” he says. “I was off work for three months, and in those three months I heard about an Aboriginal music course in Adelaide. I always had the spirit of music in me, and so I thought, ‘Well, if I’m sitting around for three months, hey, let’s try Adelaide Uni’.”

ABSTUDY – the federal scheme giving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students fortnightly study payments – funded the 28-year-old’s audition flights to Adelaide. Without financial help, Grayson says he would not have made the trip. He remembers Doug being his audition lecturer, who watched him play a “terrible” cover of a Stevie Ray Vaughan blues guitar piece. “But Doug seemed to think, ‘That’s ok’,” he says, laughing.

Relocating to Adelaide and studying full-time was a shock to the system. Not because of the higher education system, but because Grayson’s Aboriginality was being celebrated in the classroom. This was not his experience on the Gold Coast, a city with beautiful beaches, a cosmopolitan skyline and, according to Grayson, “systemic racism across the board”.

“It was really about assimilation,” he says of his former home. “And they wanted to undermine any cultural heritage in terms of customs and practices.

“The education system was always about keeping you down, mocking you for your culture, and was designed for a particular purpose, and it wasn’t for us. So, coming to CASM, to Adelaide, [it] was an amazing culture shock for me. Not only did they encourage and support the concept of Indigenous knowledges and songs, and culture – they embraced it.”

Jardine was one of Grayson’s teachers, and says he immediately recognised a spark in the young musician’s ability. Not just his performance chops – though he was a “bloody good” guitarist, Jardine says – but his potential as a teacher.

After Grayson completed his three-year CASM advanced diploma and a subsequent contemporary music degree at a Byron Bay music school, Jardine saw his opening – he was not going to let Grayson slip through the institution’s fingers.

“On the day he finished his course, who rings him up? Me!” Jardine says, smiling. “I say, ‘So what’s happening? I’ve got a deal for you’.”

It was a full-time position at CASM, which didn’t immediately sway Grayson. “He says ‘I don’t know, I have to think about it. I have to talk to my wife, think about the kids’,” Jardine recalls.

Though he was rebuffed, Jardine had a backup plan.

“I was driving up to Queensland. What do I do? I stop in on the Tweed River there and pop in to see his mum and dad,” he says. “We were sitting there, having a cup of tea, having cake, and having a yarn, and I told them I wanted Grayson to work.

“They rang him up straight away and said, ‘There’s somebody who wants to talk to you’, And he goes, ‘Who’s that?’ but then goes ‘I’ll be there in five minutes’. He comes around, and then he knew he got stuffed.

“And I said, ‘Well, if you want something done, mate, this is how you do it’.”

Grayson bucked his mentor’s expectations. He didn’t take to teaching, hating it initially. But this outlook changed when Grayson taught a student from Nhulunbuy in the Northern Territory. This student, Johnny Ryan, wasn’t prodigious, in fact he stopped showing up to class.

Johnny called Grayson relentlessly. Grayson believed the young man, who “would sit in the class, look stupid”, wanted to come back to CASM. Grayson rejected his calls every time. But one day, Johnny got a call through and dropped a bombshell.

“He said out of all the teachers he’s had, I was the one that stood out because I cared,” Grayson says. “And he said that he named his child after me. I thought, ‘This is insane. This is actually a very, very important role here’.”

Aboriginal country musician Nathan May studied at CASM from 2012 to 2015 and remembers Grayson for his “tough” teaching style. He says Grayson is the reason CASM continuously churns out impressive First Nation talent, such as recent alumni Zaachariaha Fielding, Ellie Lovegrove and Simi Vuata.

“Grayson’s influence with Aboriginal peoples and Aboriginal musicians that come through CASM has been pretty influential in terms of people having a career in music and finding what path they want to be on,” Nathan says of the man he refers to as a mentor.

Nathan is an Arabana, Yawuru and Marridjabin man hailing from Darwin, and over a decade ago was looking for an alternative to the “vicious cycle” people his age were getting themselves into – “drugs and alcohol and violence,” he says. Nathan heard about CASM and journeyed 3,000km south.

He believes studying with an all-Aboriginal cohort bolstered his confidence, and now he doesn’t flinch in higher educational settings as an Aboriginal man.

After CASM, Nathan enrolled in the Elder Conservatorium’s Bachelor of Music, where he says he is often the only Indigenous person in the lecture theatre. But in this very white, very old space, Nathan is proud of the colour of his skin. “I wasn’t afraid to show people my culture,” he says.

Tilly Tjala Thomas completed her CASM Foundation Year in 2021. Around this time, the award-winning neo-folk Nukunu musician released her song ‘Ngana Nyunyi’, and she wanted to be around other First Nations people involved with music and culture. Looking back, Tilly says studying at the centre was one of the best things she has ever done.

“I felt accepted,” she says. “A lot of it has got to do with the support and just being engaged in class… and just being able to embrace your culture and not feeling like you have to put yourself in a box.

“I felt like I was just myself when I was there.”

Unlike Nathan, Tilly says she didn’t feel as comfortable as a First Nations woman in the Elder Con’s Bachelor of Music program when compared to CASM. She also didn’t find it as fun or engaging.

“I deferred my pop music degree,” Tilly says, adding she wanted to focus on her burgeoning music career. If CASM had a three-year degree, Tilly says she would sign up in a heartbeat.

CASM has changed significantly in its half a century of being. The music centre no longer shuttles its students from the Adelaide CBD to the APY Lands. Long gone are the days of rehearsing in soup kitchens and disused boat sheds, as CASM now has dedicated performance facilities. Due to funding cuts, the department now only boasts an average of seven students – a sliver of its former highs. But there is one thing that has remained in the halls of this one-of-a-kind music department: soul.

“It’s not just strumming the guitar,” Grayson says. “We also did things like going to jail and we’d go and do performances in correction centres and go and talk to Indigenous youth.

“The whole principle around CASM isn’t about just performing [or] just about learning language. It’s networking and bringing the community in, but also going out and teaching the community about this amazing thing that can empower people.”

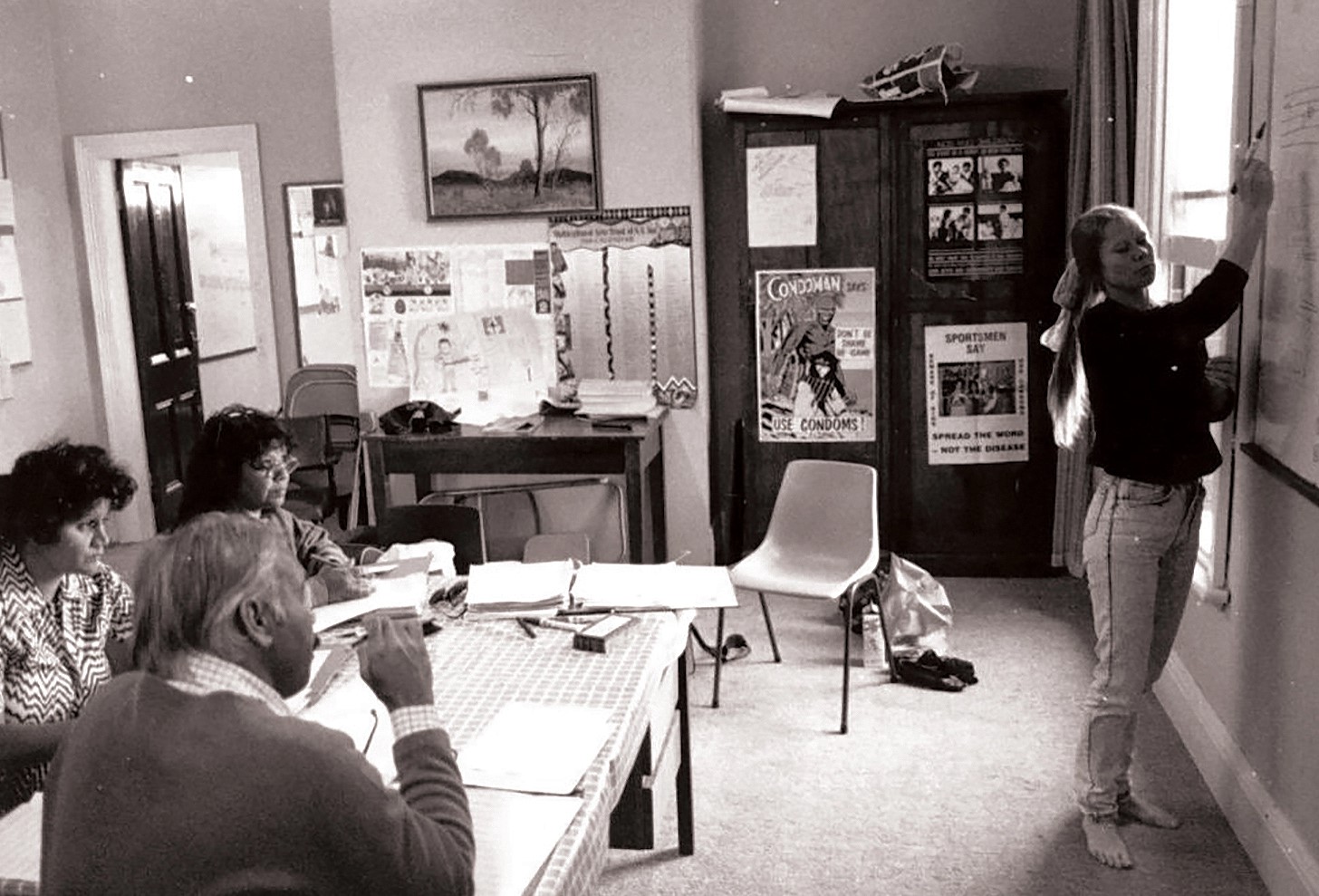

Jenny Newsome teaching music theory to Sid Graham and Rose Page

In the final edition of Tjungaringanyi, CASM’s newsletter, printed in 1992, Rose Page published lyrics to a song we presume she wrote, called ‘Freedom’.

Much like CASM, the song embodies an ambitious spirit, wanting to preserve culture: “We’ve survived and we’ve come a long way / We’ve survived and we’re going to stay”.

Words: Angela Skujins

Images: Supplied