Internationally-lauded composer Julian Cochran has enjoyed a rich career in classical music and now, he’s brought a taste of European culture to Adelaide in stunningly lavish fashion.

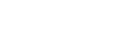

On Tynte Street in North Adelaide, sandwiched between a Thai restaurant and a web design business, sits a little, single-storey 1885 bluestone terrace house. So understated is it, you could be forgiven for not looking twice, except perhaps for the front door, which has been painted pale pink.

This heritage-listed facade is sweet, but tells nothing of the splendour – almost other-worldliness – that reveals itself when you open that candy-hued door.

Exquisite Italian grey and sepia stone tiling and Rococo archway greet you first. You then walk past a mirrored overflow room, before reaching the main hall, with its breathtakingly ornate soaring ceiling, light blue walls, intricate white plaster detailing and checkerboard floor.

What was once an old accountancy office has been reborn as the North Adelaide Concert Hall and is the creation of Julian Cochran, a classical composer who is so inspired by the gravitational pull that beautiful concert halls hold on audiences that he wanted to create something similar in Adelaide.

Julian, who was born in Cambridge but spent much of his youth and 20s in Adelaide, has spent the past 20 years visiting concert halls in cities such as Saint Petersburg, Amsterdam and Genoa as part of his work.

“I would hear young ladies and gentlemen – in their 20s – in Saint Petersburg say, ‘Let’s go to the Mariinsky tonight’, without even asking which ballet or opera was there, just citing the hall itself,” Julian says.

“I became interested in taking photographs of every corner of these beautiful concert halls, paying attention to such things as how the ceiling coving was constructed, the amount of plaster used within the decorations and the three-dimensionality of the sculptures.

“Using these designs, I selected an old accountancy office, which had gone through a failed renovation, as the ideal location in North Adelaide for the concert hall and essentially built it from scratch.”

What’s more impressive, Julian did it all while living in Saint Petersburg, sending more and more of his concert hall photographs back to his builder, Jim Diamanti in Adelaide, showing them what was possible.

The result is a transformed building, reminiscent of 1700s Baroque architecture. Completed in 2022, only the frontage of the original 1880s bluestone remains after the two-year construction.

Julian says at times he barely believed the jewellery box coved ceiling was possible, even making a paper model for himself to prove that the pinch points would be hidden by cornices.

Julian explains the result: “The exterior has a humble appearance, and then you enter into a divine world, a fairy tale.”

Among the stunning features of the space are four roundel sculptures by Danish sculptor Thorvaldesen, which represent the four seasons. In parallel, the blossoming of a girl through four stages of her long life.

But it’s the 11-metre long ceiling fresco which is staggering in its intricate detail and impact.

“The ceiling was the final step and it came about after meeting (artist) Fabio Pratio by chance whilst I was strolling through nearby Genoa and saw him with his brush at work through a window,” Julian says.

“We made friends and it turned out that he restored many of the Italian palaces for the state, so he painted what is now the entire North Adelaide Baroque Hall ceiling with the original lime technique while he was still in Italy.”

Fabio’s ceiling was then disassembled and shipped to Adelaide, where it was reassembled as the crowning glory of the hall.

Growing up, Julian recalls there were so few opportunities for classical musicians to perform in a professional setting such as this.

Julian in Warsaw helping Chopin Competition prize winner Andrzej Wierciński prepare to perform Julian’s four-part work for soprano and piano, Night Scenes, at the Polish Radio Concert Hall.

“They are trained over so many years and then thrown into our neoliberal world where anything that doesn’t make a profit is degraded and treated as second-class,” he muses. “The idea of playing at the Town Hall was almost out of the question, with it being such a closed, protected world. So, I have turned that upside down by giving the talented and ambitious graduates ample opportunities, and professional support, to perform alongside the more socially-connected musicians.”

A French Baroque harpsichord sits in the hall, on loan by Flinders University. The German hand-crafted piano is the same Steingraeber model supplied to Hungarian composer Franz Liszt in 1886 and is considered by many as the pinnacle.

Recitals are held each Saturday at 1pm, Thursdays at 1pm and longer recitals at 7pm.

Julian says the hall has exceeded his expectations and he aims to gradually pass on the administration to volunteers so he can concentrate on his own composing.

Julian’s career has been rich and successful, beginning in the 1980s with a piano performance scholarship at the Elder Conservatorium at 14 years old.

A year earlier, in 1988, Julian had taught himself computer programming and over four years, he invented games that were successful around the world, which he says taught him to plan and complete projects with his own initiative, an essential step to being a composer.

Julian would play all of the acoustic instruments in front of microphones onto a tape, turn the lights off and stay up all night in his own world, listening to the sound combinations.

“I was so obsessed that I would need to skip days from high school just to catch up on sleep.”

At 18, Julian stopped recording and tended towards the written manuscript, knowing written music would transfer its value over time far better.

“Many of Bach’s works are written to be performed privately by the harpsichordist rather than performed to the public – it is the experience of performing itself, involving discovery and deep aesthetic intrigue, that is part of the purpose of music.”

That said, Julian’s music is today performed by pianists, chamber groups and orchestras around the world. In Warsaw, there’s an annual music festival and competition centred around Julian’s music and in Russia, Julian says the level of appreciation is enormous.

“Being there is like being a cricket player here,” he says.

Julian’s drive comes from the hard work itself. “As you construct more ideas, and clarify more, the meaning is formed within the music itself rather than requiring references to the outside world.

“If you imagine a child building a castle, they start by dabbling and the ideas form as they work, with the former work providing inspiration for what follows – and in the end it has clarity, completeness and purpose.

“When you ask the child ‘what inspired you’ the answer is the experimentation itself. I can improvise at the piano for hours, producing endless ideas, but this is, in a sense, like the child’s dabbling. Sometimes if you are lucky, a whole section of music – an exposition – can be spontaneously produced during this process, and a second contrasting subject may be added later to produce a short composition rather quickly.

“But usually works are larger and require months to compose. They start with a musical idea – a motif – and you develop the motif by varying it in endless ways, such as upside down, or in different harmonic or atmospheric contexts.

“Gradually large musical themes develop from these motifs, much like the flowers of a garden emerge in stages from their seeds. In the final weeks of a larger composition, the level of intensity of focus becomes incredible.

“You are going to sleep repeating the phrases and when you wake up, remarkably, you are still sometimes repeating them. It can take many months to compose a work yet it is written out in about three days, and I do not even have words to describe the sense of elation when you see it written down.

Julian’s Monaco apartment, complete with a view to the sea that extends to Italy.

“This incredible feeling lasts for quite a few days before you move onto the next work. You are then faced with a black void – there is nothingness ahead, and yet you must start again and create a new world of meaning again out of this nothingness.”

These days, Julian’s composing is all done from Monaco. He relocated there out of necessity – he was travelling to Europe three times a year to assist conductors and give piano lessons to those recording his music.

“I always loved road cycling in Adelaide and in Monaco, it is like a dream in this regard, with the French alps literally ending right at my apartment.”

Julian says his apartment is small – much of it taken up by his Bosendorfer piano – but it’s all he needs.

“Monaco is ideal for composing because, besides the exquisitely clear sea and the ominous alpine mountains all the way to Genoa, and the beautiful Belle Epoch architecture everywhere, you still have the conveniences of a lot of cafes, and there are shops and restaurants with normal prices once you get to know Monaco.”

When Monaco cools, Julian enjoys coming back to Adelaide for our warmer months.

Julian says one of the most wonderful parts of what he does is the letters he receives from musicians who perform his music.

From a pianist in Moscow: “I’m convinced that your new works will be as bright, deep and original, as all your art, and the name of composer Julian Cochran will take its place on the Olympus of outstanding composers of the XXI century.”

The French harpsichord that sits in the hall was built and decorated by Richard Schaumlöffel after Pascal Taskin, 1769, lent by Flinders University.

This article first appeared in the September 2023 issue of SALIFE magazine.

Words: Zoe Rice