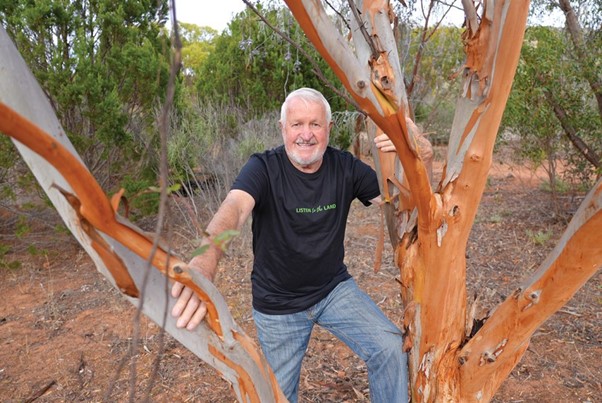

Prolific plant author Neville Bonney might be aged in his 80s, but his passion for educating people about the importance of seeds and native plants shows no signs of slowing down.

A desert oak cone and its seeds.

Much has changed across the South Australian landscape since colonisation. Land clearing and urban sprawl, while the introduction of exotic weeds and farm animals have contributed to widespread native plant and vital habitat loss.

Thankfully, organisations such as Greening Australia and Trees for Life, along with a host of other regional volunteer collectives are assisting to help halt and, where possible, reverse the impact and degradation on bushland and local ecosystems. Among these groups are individuals who have become “agents for change”, reaching out to the wider community to share knowledge and make a difference.

A recent recipient of the SA Environment Awards Lifetime Achiever, Neville Bonney has dedicated his life to highlighting the importance of conservation, in part through the promotion of Australian native plants in both word and deed.

Now in his early 80s, this plant pioneer, prolific author and ethnobiologist (studying the dynamic relationships among peoples, biota and environments) has no intention of slowing down.

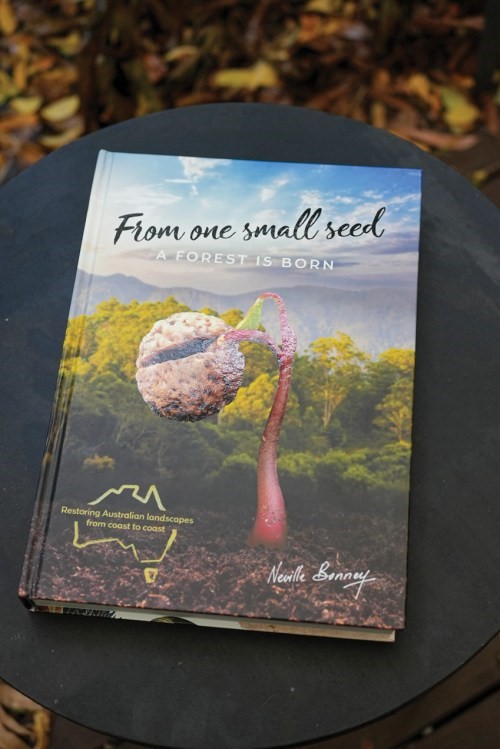

The cover of Neville Bonney’s new book From one small seed: A forest is born.

Neville’s connection with the land took root as a young boy, back in the 1940s, spending time with his grandfather amongst the once expansive Stringybark Forest on the Mount Burr Ranges in the South East of the state. Mature trees – and a vast array of understory plants – provided the perfect habitat for pollinating insects and diverse birdlife creating a sensory experience that simply entranced a young Neville.

Strong as that pleasurable memory was, the subsequent sight and sounds a few years later of cracking branches and screeching birds when bulldozers cut swathes of this sacred bushland, became an even stronger memory. He witnessed the isolating of the once busy wildlife corridors, pushing flora and fauna to the brink; an all-too familiar sight in so many other regions across this state. Though painful, that memory has been an impetus for Neville’s constant environmental crusade.

“Listen to the land” is an oft-used phrase that resonates with his Indigenous heritage. As trees and shrubs were removed, their seed remained to germinate, sprout and, when left unhindered, grow and repopulate. The importance of seed in land rejuvenation saw Neville head bush to commercially collect seed from a wide range of native plants and help further his love and knowledge of these precious plant embryos.

Never one to let the wallaby grass grow under his feet, Neville has run his own native plant nursery, been involved with Greening Australia and TAFE SA.

Neville has been passionate about the environment since growing up in the 1940s.

What seed is that?, written by Neville and first published in 1994, was the culmination of years spent in the outback identifying plants and gathering their important seed. Regarded as a “must-have” for anyone interested in revegetation, a revised and updated edition of the book has proved its popularity.

As the saying goes, the best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago … and that is exactly what Neville did on the property of his good friend and fellow keen conservationist, John Del Fabbro. Located on the outskirts of Palmer, a town just east of the Adelaide Hills region, the six-hectare Kitticoola Dryland Arboretum has been an educational and functional demonstration of regenerative tree farming.

The past two decades have seen this semi-arid space become home to many edible Australian native foods, medicinal plants and rare inland species. Desert fig, sandalwood, quandong, desert oak, arid Eucalyptus species, and many more, are successfully growing in this harsh environment demonstrating their potential for commercial dryland farming options.

Workshops run by Neville at the Kitticoola Dryland Arboretum provide attendees the unique opportunity to experience its joys and special flavours. Picking finger limes, sampling Sandalwood nuts, harvesting muntries, plus making and drying wattle seed cakes, are all part of the edible bush journey. Eating produce from plants adapted to local conditions makes sense, especially when it has been an important part of the diet of First Nations peoples for thousands of years.

The small-growing Eucalyptus macrocarpa.

Neville is a strong advocate for the production and development of markets for native edibles in Australia and internationally. Quandongs are a key plant in the arboretum as they continue to gain mainstream popularity. While growing and fruiting happily in the wild, domestic cultivation and harvesting spans a mere 50 years, so there is still much to learn about the horticultural intricacies of this authentic bush food.

Visitors to the arboretum not only enjoy a full bush immersion, they also get to spend time in a historic place. In 1845, gold and copper were first dug at Kitticoola, one of South Australia’s oldest mines. In its heyday, some 400 people lived on site and the school catered for up to 60 students, although only a few crumbling ruins remain as a reminder. While majestic river red gums can be found lining the lower creek and billabong, sadly their long past relatives on the upper slopes were felled for fuel and building materials.

Neville describes Kitticoola Dryland Arboretum as, “once a valley of gold and copper, now a collection of rare Australian trees and shrubs”.

This bush botanist believes he has created a special semi-arid zone ark, destined to become an important centre of knowledge in answering the question “What Australian plant species are best suited to survive in the face of creeping climate change?”. As once temperate regions transition to lower rainfall and hotter summers, understanding which plants perform under these conditions means appropriate Australian native trees plus shrubs can be selected and added to the landscape allowing years of establishment ahead of impending heat waves.

The Kitticoola Dryland Arboretum is a six-hectare space filled with semi-arid-suited plants.

Always looking to educate, Neville’s latest book, From one small seed: A forest is born taps into his passion for growing plants. It covers a gamut of topics including the importance of seed diversity, flower pollinators, checking seed viability and germination techniques. This comprehensive guide to Australian native plants is filled with photographs of flowers, fruits and seeds making the identification of more than 700 species so much easier.

Neville has tapped into the renewed interest in Australian native plants, whether you are a novice, experienced bushy, or simply a plant enthusiast, this book is a rich seed resource on how to collect, what to collect, when to collect and how to propagate and plant. The clear message is every seed is the basis of new life in restoring our fragile landscapes whether they be wetland, woodland, forest, desert or grassland.

The “Healthy Bushlands need Fungi” chapter describes the symbiosis between plants and fungi and how nearly all plants depend on fungi to populate their roots providing pathways for essential water and nutrients. Once plants are removed, the symbiosis and connection between plants and fungi is broken and not easy to repair. The same applies to plant reliant ecosystems, where the clearing of nectar producing cultivars such as grevilleas under a tree would see birds like honeyeaters look elsewhere for their food and completely alter the ecological balance of that locale.

Adding flowering native plants to the veggie garden is not only attractive, it encourages a broader range of insects and improved pollination.

Desert oak are dioecious, having separate male and female trees.

Neville firmly believes that placing environment high on the agenda within our current education system will reap great rewards. A healthy environment and healthier society are not a choice, but a responsibility. Look after the land and it will look after us.

From One Small Seed is available for ordering via nbonney@senet.com.au.

This article first appeared in the August 2023 issue of SALIFE.

Words and Photos: Kim Syrus